DIY Add Line Out to Your Guitar Amp

The Problem: you want to tie your guitar amp into the sound system, but your amp doesn’t have a line out.

A friend of mine has a Line6 Spider IV 120W with no outputs other than the speaker and headphone. We looked at hacking the headphone out, but decided not to carve into the brand new amp as it would require cutting the circuit board. The solution: a direct box off the speaker.

What’s a direct box?

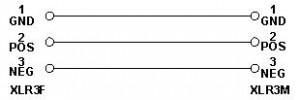

A direct box is simply a transformer. It usually has a high impedance side with a 1/4″ jack and a low impedance side with an XLR microphone cable for balanced signals. Normally they are used for small signals like an acoustic guitar pickup or a speaker (or computer) line out. They can also be used to large signals if you cut the signal down to what your sound board is expecting.

Danger!

Direct boxes exist with a “speaker” level switch which provides 20dB of attenuation and a GND lift switch to disconnect the input ground from the output ground. One of these boxes could do the job correctly if all the switches are set correctly. But, modern bridge drive solid state amplifiers (such as the Line 6) could be shorted out and destroyed if the ground switch is in the wrong position because they might short one side of the speaker to ground.

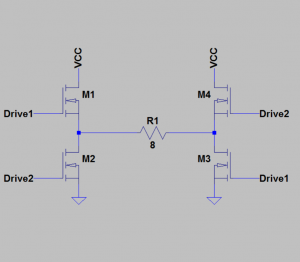

A bridge drive works by driving both sides of the speaker so that one goes up while the other goes down,

If you connect either side of your speaker to ground (like through your direct box), you short out one side of the driver and will likely damage the amp.

More Danger!

The signal on the 8 ohm speaker for 12W (half volume for our Spider IV) is 9.8V peak which is a wee bit high for the mixer.

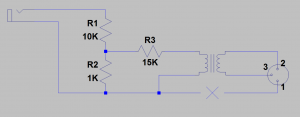

We want to cut that down to 1 V (-20dB) so we put a resistor divider in there. Also, we add a series resistor to bring the resulting output impedance closer to the 600 Ohm standard for balanced line mic cables.

The exact attenuation isn’t important, so I used easy to find resistors to make a divide by 11 circuit (-20.8dB). A true divide by 10 would use R1 = 9K.

If you are interested, the transformer we are using has a 6:1 turn ratio and the output impedance will come out about 440 Ohms which is close enough to the 600 Ohms.

Build it:

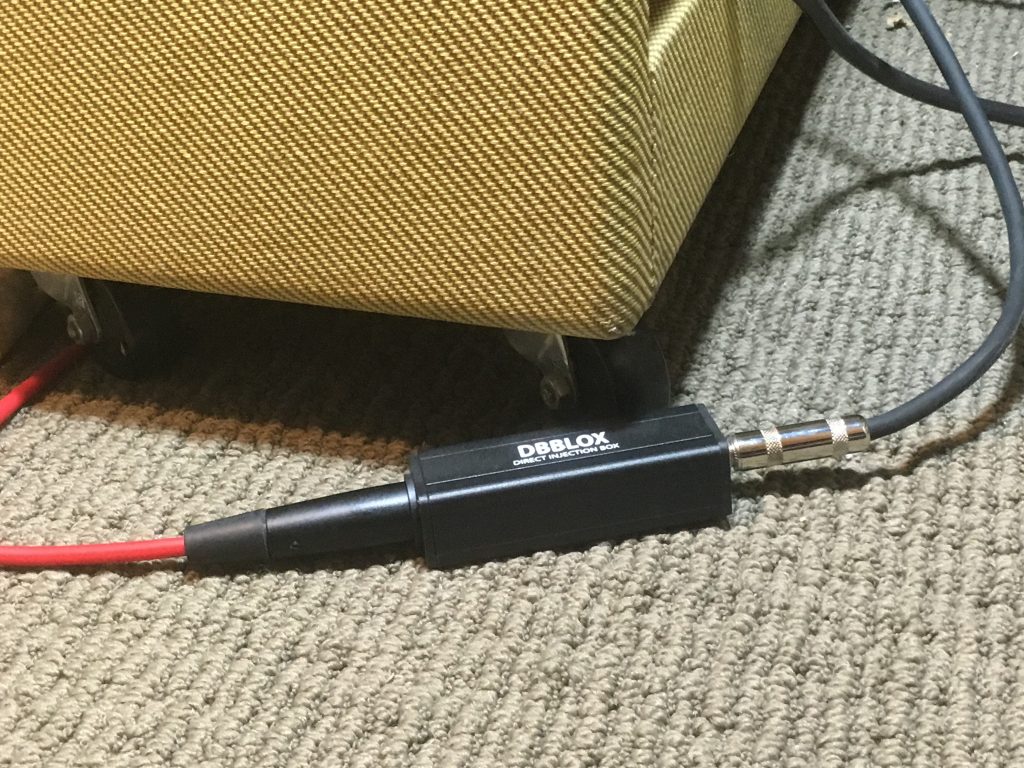

I didn’t want to throw away any expensive features, so I bought a simple direct box: RapcoHorizon DBBLox. The only modification needed is to remove the ground wire and add the resistors.

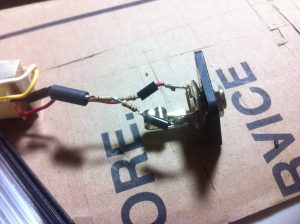

I cut out the wire from pin 1 on the XLR connector. The connectors themselves are mounted in plastic panels so they are already electrically isolated from the chassis.

Then I inserted the resistors with some heat shrink to cover them and keep the contacts from hitting the metal housing.

Last put it all back together. Keep the wires for each side of the transformer wrapped with themselves as close as possible – this picture shows the black and red separating a bit too much. The direct box will be prone to some hum and keeping the wires together will help.

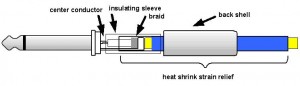

Next you need to connect it to a speaker. You need to use a shielded cable for this part so I used the good half of a damaged guitar cable. I crimped a quick disconnect onto the center conductor and rolled the shield together for the other connector (insulate with heat shrink). Leave enough lead length to hit the spare speaker tabs on your amp.

That’s it! Connect it up and give it a try. I started at low volume to make sure the levels were good and nothing had gone wrong. Eventually I will velcro it into the back of the cabinet so I don’t have to go hunting for it.